Working Percheron Horses

of the Garden Route Indigenous Forest

Percheron Horses originated from the Le Perche region bordering on Normandy in northern France. They were recognised for their cooperative character that revealed itself in their way of being good natured, strong and brave, yet obedient and quick to learn.

Due to Arab influence they also were noble looking horses with a refined head, delicate ears and dignified gait. As draft horses they stood between 16-18 hands high and weighed between 770 – 1000 kgs. Typically they are born black and get lighter as they age, becoming white by 12 years of age.

The Distinctive Role of Percheron Horses

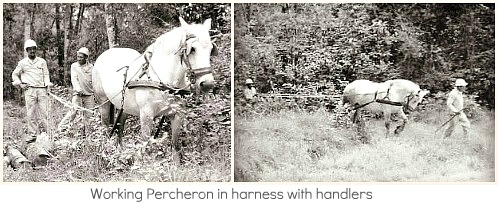

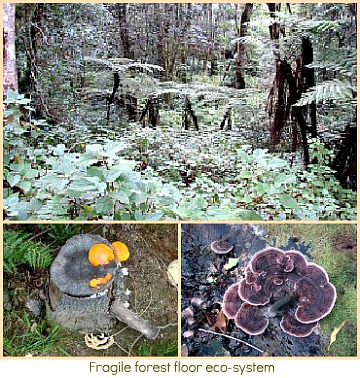

To minimise the impact on a sensitive ecosystem, the Department of Forestry used Percheron Horses to haul timber out the forests to roads where regular custom built vehicles could deliver them to the nearest depot. The indigenous forests were harvested according to strict conditions imposed by the International Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) that certified that they were being managed in a sustainable way.

After being systematically divided into sections, trees were selected for harvesting that were gauged to be in the last 10 years of their life cycle where visible signs of “senility” were detected i.e. trees that were diseased or dying. A particular section would not be harvested again for at least another 10 years.

Thus Percheron Horses played a distinctive role in the Garden Route Indigenous forest management in South Africa for several decades.

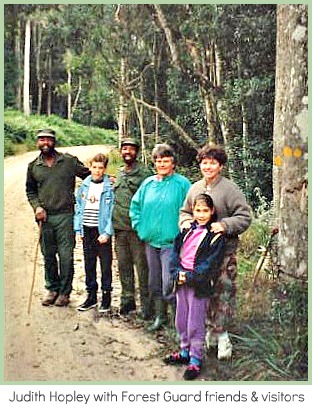

Judith Hopley was a registered Tour Guide whose speciality was the indigenous forest. She got to know a number of the forest guards and some of the handlers of the Percheron horses. She says she respected their knowledge of the forest and their dedication to their work.

These men spent most of their days and a good number of nights in the forest and understood many of its secrets. Because of her sincere interest and love of the forest, they shared some of its mysteries with her.

At the time, the Department of Forestry employed a sizeable herd of Percheron horses that, along with their handlers, had been trained to work throughout the State forests. The technique was called slipping. The horses would be led to felled trees and then harnessed to logs that they dragged back along slip paths.

Some slip paths were made for this purpose. Others were well-trodden paths that criss-crossed the forest.

They had been created by decades of woodcutters, who had tramped the same tracks as generations of elephant herds before man's presence wrought its' destruction on them.

From broader forest tracks a specially designed log-carrier tractor transported the timber to the nearest road at the edge of the forest from where it was loaded onto trucks.

This method proved to cause

the least environmental damage to the sensitive forest floor because the root hairs

of indigenous trees are relatively close to the surface where they obtain most

of the trees’ nourishment and if they are crushed by compacting the earth on top of them, the tree will die. For the same reason, harvesting timber this way only took place in dry weather.

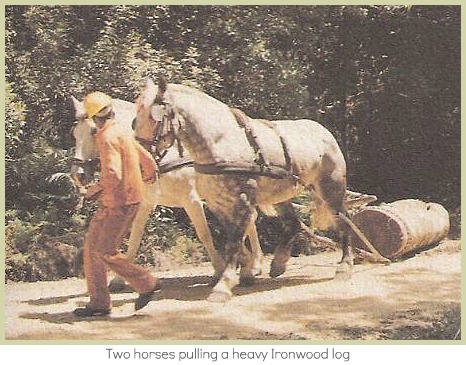

One day Judith witnessed a handler with his Percheron that was straining to haul a heavy ironwood log. Standing beside his horse, the man quietly instructed in Afrikaans, "asem"– breathe. He rested the horse for some minutes, then instructed "trek" – pull!

The handlers of the horses were carefully chosen and very well trained. They had a close relationship with them and knew the capabilities of each one. The handlers were very proud of their charges and often decorated them with a ribbon tied around a fetlock for example or entwined in a piece of mane.

Techniques were instigated to assist a horse manage a heavy load. If a log had to be retrieved from the bottom of a steep gully, a tyre would be wrapped around the trunk of a strong tree at the top of the slope, to prevent it from being damaged.

A cable would then be attached to the log, extend around the tree protected by the tyre and fastened to the horse that was facing down the incline. It was easier then, for the horse going downhill, to pull the log up the slope. At times, 2 horses could be harnessed in tandem to haul a single large or very heavy log.

On one occasion Judith was at a vantage point from where she witnessed a herd of about 10-12 horses being moved from the Farley Forest to Goudveld. One handler rode bareback on a Percheron and the other horses cantered freely behind. A number of trainers ran with the herd.

The sound echoed through the Homtini valley as the big beasts loped through it and up the other side to Goudveld – she said it was an extra-ordinarily splendid and moving sight.

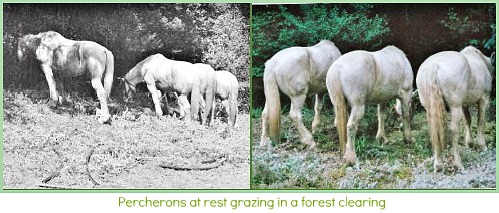

A team of 6-8 horses would often work in the same area of the forest for several days. If their paddock was too far for them to return to, they would be corralled in an open area at night by a role of wire that was stretched around a number of trees to keep them in.

They would be allowed to graze, be given water to drink, and a big bale of lucerne. Once they were finished working in that particular area and it was time to move on, the wire would be rolled up so it could be used again.

Extraction by Sikorsky Helicopter

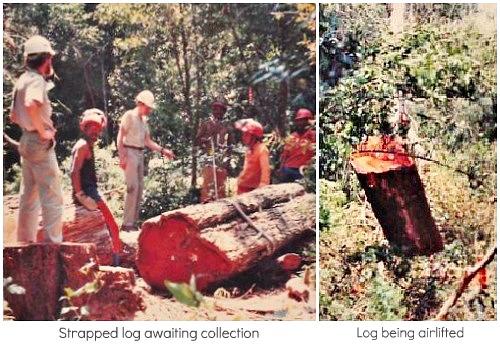

One or two days a year, a Sikorsky helicopter would be hired to airlift out expensive timber that was in an extremely difficult place for the Percheron horses to get to or too heavy for them to drag out.

With the cost mounting by the minute, it was estimated that it could take up to 10 minutes to move a log to an accessible collection point for the logging trucks.

All preparation for this day was done in advance.

The area around the selected tree was cleared of anything that might entangle the cable or endanger the men on the ground.

It had to be a clear day with good visibility for both the pilot and the groundsmen and there had to be no wind.

It was always a fairly hazardous operation.

Once the helicopter had left the depot and was in the target area, a flare would be sent up to indicate to the pilot where the log was.

As the Sikorsky hovered, a steel cable was lowered and a man on the ground would run in and attach it to the log that had a strap around it.

This would tighten around the timber as the helicopter pulled it high into the sky flying off to deliver it back to the access point where another groundsman would then release the cable and the helicopter would fly off to the next log.

There was a safety mechanism that allowed the helicopter to detach the cable if it got stuck anywhere among the trees. Time was of the essence and the helicopter only landed to refuel.

It's all History now!

Sadly all that is now past and the Percheron Horses have been relegated to a part of history. About 20 Percheron horses were sold off to PG Bison which operate mainly Pine with some Eucalyptus plantations around Sedgefield and George.

They have engaged in a breeding programme at their Groot Brak River Estate using Percheron mares crossed with Spanish donkeys.

The resultant mules are found to be ideally suited to the work of low impact skidding. The mules are calmer than the big Percherons and work steadily for up to 8 hrs a day causing no soil compaction and minimal damage to standing trees. They are proving to be a cost effective and eco-friendly method of extracting thinnings from plantations.

A local horse rescue unit make routine visits to the estate and a PG Bison team does regular inspections to ensure standards are maintained.

The indigenous forests have for the most part been handed over to SANParks.

. The whole process from harvesting of the State forests using Percheron horses to extract indigenous wood to the auctioning of the valuable timber, was found to be prohibitively expensive and ultimately unprofitable.

How much of the integrity of the process has been retained has yet to be seen. Time will tell whether the FSC Certification is more than just a piece of paper. A BEE company has been awarded the contract to harvest the timber and one has to wonder what kind of experience they have, to do this complex job in an environmentally friendly way and how it can be profitable for them.

Once again, as in so many instances in today’s market driven, bottom-line based economy, will expediency supercede conservation practices for our imperiled natural environment? Will lack of expertise and the desire for quick monetary rewards see the demise of the Garden Route's already fragmented remaining indigenous forests?

Acknowledgements and Resources

Thanks to Judith Hopley for information about the Percheron Horses & their photos and the extraction of the timber by helicopter and those photos.

The Knysna Forest and Tsitsikamma Forests -Their history, ecology and management - Chief Directorate Forestry - Department of Water Affairs and Forestry.

PG Bison: Mule power for low impact thinnings - SA Forestry Magazine Nov 2010.

RELATED LINK

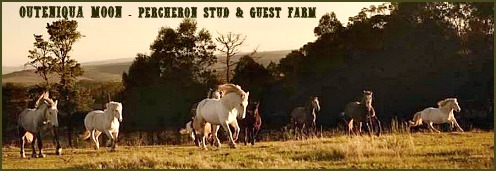

Outeniqua Moon is a magical 100 hectare mountain farm that is home to the biggest horses in South Africa. Guests can learn about these heavy but gentle draft horses, the earth they tend and have an unforgettable spiritual and practical experience with the heavy draft Percheron Horses. Day visits and overnight stays are offered.